I had some time over the weekend for a marathon gaming session and decided to take full advantage. After a couple hours of play I started to realize how fatigued my ears were getting. “Oh no, not this loudness war stuff again,” you might be thinking to yourself. Don’t worry, I don’t plan on ranting about the upward trend to make things loud. No, instead I want to take a more objective look at the current state of loudness in video games, especially compared to broadcast standards. We’ll look to the broadcast world for guidance, see some blossoming standardization from Sony, measure some games, and think about the future of loudness recommendations in game audio.

Why Loudness Matters

Loudness standards are important in an environment where a number of third party groups are contributing content to the same platform. This certainly applies to video games and game audio. As sound designers and game publishers, we want the end user to have a consistent experience when it comes to loudness levels.

Not only should game audio have a baseline for loudness, that baseline should correspond to established standards in television and film. The goal is a consistent experience when switching between movies, television, and games, especially with the next generation of consoles where users have easy access to all these types of media from one unit.

The Standards (Or Lack Thereof):

Currently, there are no widely accepted standards for measuring or mastering loudness levels in video games. In November 2012, Sony’s Audio Standards Working Group (ASWG) made some headway by creating ASWG-R001, internal loudness recommendations for their 1st party titles.

Sony’s ASWG looked to the broadcast world, specifically the ITU-R BS.1770 specification which is used in the EBU R128 and ATSC A/85 broadcast loudness recommendations for Europe and the U.S. respectively. Measuring perceived loudness is a tricky thing and BS.1770 is an algorithm and measurement protocol that seeks to more accurately measure how we hear loudness from a given sound source.

Understanding the Acronyms: BS.1770, R128, and A/85

In order to adopt, apply, and reinterpret these standards for game audio, we need to understand a few basics about the BS.1770 specification and how it’s utilized in R128 and A/85 broadcast recommendations.

BS.1770 includes the following measurements:

- Loudness Level (at three different time scales)

- Integrated (I) – Full program length

- Short Term (S) – 3 second window (un-gated)

- Momentary (M) – 0.4 second window (un-gated)

- Loudness Range (LRA)

- True Peak Level

Both R128 and A/85 recommend integrated loudness and maximum true peak values for broadcast audio.

The R128 (Europe) recommendation is:

- Program level average: -23 LUFS (+/-1)

- True peak maximum: -1 dBTP

The A/85 (U.S.) recommendation is:

- Program level average: -24 LKFS (+/-2)

- True peak maximum: -2 dBTP

R128 and A/85 do not recommend exact loudness ranges, but typically broadcasters do. For example, a broadcaster might require a news program to have a maximum LRA of 8 LU, while a fictional drama could have an LRA up to 20 LU. For further reference, a dynamic movie might have an LRA of 30LU.

Now, let’s look at the Sony ASWG-R001 recommendation:

- Average loudness for console titles: -23 LUFS (+/-2)

- Average loudness for portable titles: -18 LUFS

- True peak maximum: -1 dBTP

Units: LKFS, LUFS, and LU

LUFS = LKFS.

In an ideal world, the ITU, EBU, and ATSC would share the same terminology, but unfortunately they do not. LUFS stands for loudness unit relative to full scale and LKFS stands for loudness, K-weighted, relative to full scale. These are absolute measurements of loudness.

LU is a relative measure of loudness. Furthermore, 1LU is equal to 1 decibel. For example, if the overall program level is -26LUFS, adjusting the audio +3dB will result in an average program level of -23LUFS.

Finally, dBTP is decibels, true-peak relative to full-scale.

For a more detailed history on loudness unit naming, see Garry Taylor’s blog.

How BS.1770 Works

In order to measure perceived loudness, BS.1770 uses two weighting filters, a relative gate, channel weighted summation, and a true peak measurement that oversamples audio to detect intersample peaks.

For our purposes here, we don’t need to get too technical. But If you’re interested in exactly how all these things work, check out the BS.1770-3 pdf, specifically pages 3-16 for loudness measurements and 17-22 for true peak measurements.

In total, using BS.1770 compliant metering gives us the following values to measure and compare:

- Integrated Loudness

- Short Term Loudness

- Momentary Loudness

- Loudness Range (LRA)

- True Peak

Linear Audio vs Game Audio

Broadcast media by its very nature is different than game audio. One is linear and the other is not. One is static, the other is interactive. Obviously it is much easier to measure a linear program. The process is straight forward: play the program from start to finish.

For games, it’s not so precise. In order to get an accurate reading, we need to measure a large section that contains a representative amount of all aspects of gameplay. For example, the Tomb Raider sample below includes an action sequence, expository dialogue scene, and a low action puzzle/platforming sequence. Furthermore, for games with linear narratives I recommend measuring gameplay sections in the proper order, so the macro-dynamics of the game can be observed. Sony’s ASWG-R001 recommends a minimum measurement time of 30 minutes, however I think this on the low side. For our purposes, each game measurement below is approximately 45 minutes of gameplay. For a cursory glance, I would consider this the bare minimum. If this were a title I was working on, I would measure hours of gameplay.

Let’s Look at Some Games!

Since I am in the US I will be measuring using the A/85 recommendation, which as of March 2013 references BS.1770-3 specifications. Units will be in LKFS, but remember LUFS = LKFS. Though some games provide audio level sliders, all games were left with their default values. Below are the VisLM-H graphs from my recorded sample gameplay. The history graph in the center displays the short-term loudness over time.

Tomb Raider

Overall Gameplay

- Integrated: -16.7 LKFS

- Short Term Max: -7.1 LKFS

- Momentary Max: -4.4 LKFS

- Loudness Range: 14.9 LU

- True Peak Max: 1.4 dBTP (OVER)

Bioshock Infinite

Overall Gameplay

- Integrated: -11.8 LKFS

- Short Term Max: -4.7 LKFS

- Momentary Max: -2.4 LKFS

- Loudness Range: 13.2 LU

- True Peak Max: 1.3 dBTP (OVER)

Skyrim

Overall Gameplay

- Integrated: -26.0 LKFS

- Short Term Max: -15.5 LKFS

- Momentary Max: -9.8 LKFS

- Loudness Range: 17.3 LU

- True Peak Max: -0.1 dBTP

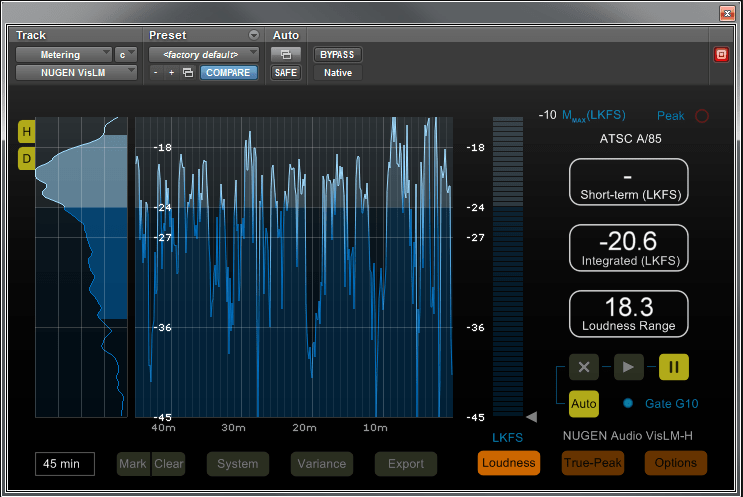

Grand Theft Auto IV

Overall Gameplay

- Integrated: -20.6 LKFS

- Short Term Max: -11.5 LKFS

- Momentary Max: -10 LKFS

- Loudness Range: 18.3 LU

- True Peak Max: -2.5 dBTP

Dishonored

Overall Gameplay

- Integrated: -23.1 LKFS

- Short Term Max: -12.1 LKFS

- Momentary Max: -3.8 LKFS

- Loudness Range: 12.6 LU

- True Peak Max: 1.7 dBTP (OVER)

Portal 2

Overall Gameplay

- Integrated: -14.9 LKFS

- Short Term Max: -5.2 LKFS

- Momentary Max: -3.8 LKFS

- Loudness Range: 13.9 LU

- True Peak Max: 0.7 dBTP (OVER)

Note: Portal 2 has frequent silent loading screens, which you can see on the history graph above. Fortunately, with the updated A/85 spec that uses the G10 gate, we don’t have to worry about cutting these out. To test this, I measured the Portal II section with the loading screens in, and once more after cutting out the silent loading screen sections. The integrated levels were identical.

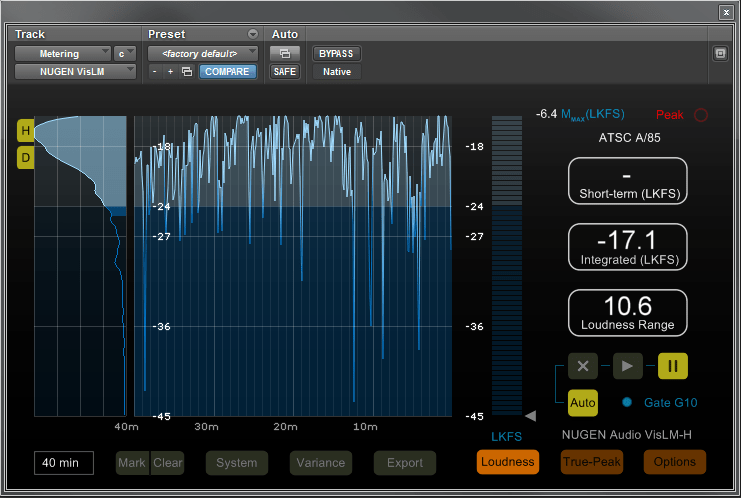

Batman Arkham City

Overall Gameplay

- Integrated: -17.1 LKFS

- Short Term Max: -10.2 LKFS

- Momentary Max: -6.4 LKFS

- Loudness Range: 10.6 LU

- True Peak Max: -1.0 dBTP

The Walking Dead

Overall Gameplay

- Integrated: -16.8 LKFS

- Short Term Max: -3.8 LKFS

- Momentary Max: -2.5 LKFS

- Loudness Range: 17.8 LU

- True Peak Max: 1.2 dBTP (OVER)

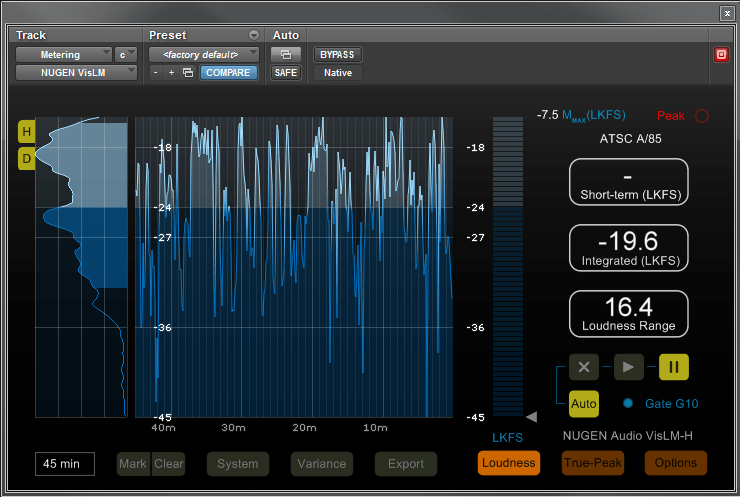

Borderlands 2

Overall Gameplay

- Integrated: -19.6 LKFS

- Short Term Max: -11.1 LKFS

- Momentary Max: -7.5 LKFS

- Loudness Range: 16.4 LU

- True Peak Max: -0.1 dBTP

The Results Are In!

Integrated Levels (Overall Program Loudness)

Let’s begin by ranking these games by their integrated levels from highest to lowest:

- Bioshock Infinite: -11.8 LKFS

- Portal 2: -14.9 LKFS

- Tomb Raider: -16.7 LKFS

- The Walking Dead: -16.8 LKFS

- Arkham City: -17.1 LKFS

- Borderlands 2: -19.6 LKFS

- GTA IV: -20.6 LKFS

- Dishonored: -23.1 LKFS

- Skyrim: -26.0 LKFS

Bioshock Infinite is clearly the loudest game on the list with an integrated level of -11.8 LKFS. The middle section where the history graph is pinned to the top is the action sequence on the Command Deck. This was the loudest section of any game. The short term levels were consistently -9 to -7 LKFS. To be fair, this is one of the biggest scenes in Bioshock Infinite, but I would still argue that the mix is too loud overall. If someone was to play Bioshock Infinite and Skyrim back to back they would have to adjust their TV or receiver by 14dB for the two games to sound similar. Likewise, a similar difference would occur between Bioshock and a TV program.

The average program level of all 9 games is -18.5 LKFS, and almost all are louder than the Sony ASWG recommendation of -23 LUFS (+/-2).

Loudness Ranges

Now, let’s move on to looking at the Loudness Ranges (LRA). LRA is just as important as overall program level. Here are the results from most dynamic to least dynamic.

- GTA IV: 18.3 LU

- The Walking Dead: 17.8 LU

- Skyrim: 17.3 LU

- Borderlands 2: 16.4 LU

- Tomb Raider: 14.9 LU

- Portal 2: 13.9 LU

- Bioshock Infinite: 13.2 LU

- Dishonored: 12.6 LU

- Arkham City: 10.6 LU

When evaluating and using loudness range to inform your mixing, keep in mind that loudness range is not symmetrical around the integrated level. One of the most helpful parts of Nugen VisLM meters above is the density graph on the left hand side. By looking here you can easily see the loudness distribution over the program length.

Also, remember that a game with a low LRA and integrated program mix of -23LKFS could be more fatiguing than a game with a higher integrated loudness and larger LRA. If a game is really loud, the user is likely to turn down the volume and conversely will turn up the volume if a game is really quiet. If the mix has little dynamic range it will sound over-compressed and lose impact.

Applying to Mixing

Obviously, not every game is going to sound the same, nor should they. Aesthetically some games will want to be louder than others. However, using BS.1770 metering can be a helpful way to understand how a mix will be perceived, and it’s a great tool for comparing games and other media.

LRA and integrated loudness can be helpful benchmarks when trying to mix within certain parameters. For instance, a handheld game should have slightly less dynamic range and an overall louder integrated level due to the limitations of the speakers and external noise factors. Knowing the loudness and dynamic range of your game’s mix is crucial.

Do Try This At Home (Or Work)

Wwise and FMOD now support BS.1770 metering. So, if you are using either one of these audio middleware tools, you can easily meter within these programs. However, if you want to measure a game directly from a console or PC you can use some of the following solutions to get audio from the game into your DAW. With all of these signal flow chains, make sure to calibrate your inputs and outputs. Play test tones on your console or PC and check the inputs to your DAW. If you’ve mixed a game before you know it’s important to check everything from the 7.1 mix to the stereo fold down.

Stereo

- Analog output to DAW

- LPCM over S/PDIF output to DAW.

5.1 to 7.1

- LPCM over HDMI to individual RCA outputs to DAW

(requires the Gefen HDMI to HDMI Plus Audio Converter) - LPCM over HDMI to AES to DAW

(requires the Arvus HDMI to AES Converter) - Dolby Digital over S/PDIF to DAW to Decoder Plugin to Metering Plugin

(for PC, Dolby Digital output over S/PDIF requires a sound card with Dolby Digital Live support)

Thanks to Garry Taylor from SCEE for recommending the Gefen HDMI Converter and the Arvus HDMI to AES Converter in this great article on Designing Sound. Also, if you want a step by step for hooking up Dolby Digital to your DAW, see Matt Bauer’s comment below.

Metering Plugins

There are a number of BS.1770 compliant metering plugins that will get the job done. Two of my favorites, which both display history graphs, are iZotope Insight and NUGEN VisLM-H.

Further Resources

Designing Sound: Different Loudness Ranges for Console and Mobile Games

Designing Sound: Video Games and Loudness Standards: Interview with Sony’s Garry Taylor

Game Audio Podcast #10 – Reference Levels

Audio for Mobile, TV, iPad, and iPod by Thomas Lund (TC Electronic A/S)

That’s A Wrap!

Please share your thoughts and previous experiences in the comments below.

Do you think there should be a general loudness recommendation for games? If so, what organization should it come from? And should it ever be enforced by console manufacturers like Microsoft, Sony, and Nintendo?

How do you mix your own games and what metering tools do you use?

Thanks for a great article. I saw your * about not getting the Dolby decoder plugin chain to work correctly. I’ve done this method for a few years now so thought I’d share my process in a Pro-Tools HD environment.

1) Optical out of your console goes to the optical in of your Avid (Digi) interface.

2) Make the appropriate I/O settings in the hardware setup to route the audio to a stereo channel. (or stereo Aux input, up to you)

3) Make sure your hardware sync is set to optical. You are now using your console as your master clock. If you don’t do this you’ll get drop outs quite frequently.

4) Insert the NEYRINCK SOUNDCODE FOR DOLBY DIGITAL plug-in on your stereo track.

** If you routed it to a regular stereo track, you can record the digital bit stream which will sound like very loud noise, if you routed it to an aux then you’re obviously just passing it through that track.

5) Set up the real time decoder plug-in of NEYRINCK to what you want to decode to (5.1 or stereo usually)

6) Route an AUX send of the output of that track to either a new 5.1 track or 6 mono tracks panned accordingly.

7) Now you can record your decoded signal, and route that through whatever metering plug-in you like.

* I like Nugen VIS-LM and iZotope Insight.

Enjoy….. Feel free to contact me if you get stuck and want some help.

-Matt.

Thanks so much for the reply Matt.

Originally, I was trying to go into an older MBox 2, which has coax S/PDIF input, so there was an optical to coax s/pdif converter in the chain. I surmised that this was probably the problem, as I was just getting noise that the decoder couldn’t decode.

After your post I went into the studio and tested it out again with a 192 and everything works great. I am also using the Neyrink SoundCode Dolby Digital decoder.

So, I went back to trying to use the Mbox 2 with the converter, and now that is working too. I must have been doing something dumb. Or perhaps, the converter is not very reliable and the bitstream is getting messed up or altered somehow.

Thanks for laying out the steps so others can see.

-Stephen

Nice article.

I can relate to your comments in the “Applying to Mixing” paragraph when considering the distribution of spoken word, podcasts, and video, distributed on the internet. Generally I advocate -16.0 LUFS as a distribution target for reasons that you clearly specify:

“… should have slightly less dynamic range and an overall louder integrated level due to the limitations of the speakers and external noise factors.”

Again, good read.

-paul.

Yes, all games can be mixed close to the same levels.

It requires mixing in a properly calibrated mix room, by a competent experienced mixer.

We do it for TV every single day.

Hopefully they will adopt the same type of standard to films soon, because they are becoming unbearably loud.

[…] Lately, audio normalisation has gained importance among the field of game audio; Wwise and FMOD Studio now support loudness and true peak metering. I won’t talk in details about that here and there are already great articles about the subject on the internet. For example, Stephen Schappler, sound designer at NetherRealm, wrote a very informative article about loudness in video games, called Listening For Loudness In Video Games. […]

Thanks for this insightful and interesting article Stephen. I’m a lecturer in the UK and will point some of my guys to your words here. I do think we need a general loudness recommendation for games. I personally love GTA and the sound design is superb. One of the factors which makes it so great for me is the dynamic range in the game which is highlighted by your research here. Cool stuff

Thank you so much for this amazing article. It was informative and concise, I enjoyed reading it and checked the related documents. Do you have any insights related to average levels for dialogues in games?

Thanks again!

This is very useful and for game composers like myself.

Thank you a lot for your incredible article.

Great article indeed.

Thanks a lot for sharing!